From, and to, the agraharam

It was less than a mile to Sengottai when the driver asked me where paatti’s—my maternal grandmother’s—home was located.

I told him that it was right behind the post office, and that we had to enter through the narrow alley that is adjacent to the post office.

He said that meant the house was in the agraharam.

I shrank a tad in my seat.

Later that evening, we checked into a hotel at Courtallam, after viewing the Five Falls and the main waterfalls.

In the morning, when checking out of the hotel, the 30-ish man working there, who knew that I am an American from the passport details that I had to provide, asked me where I was from. It is not without reason that people in the US want to know where I am from and so do people in India. Speaking in Tamil, I told him that I was visiting this particular part of Tamil Nadu because of paatti’s home in Sengottai.

He said that he too was from Sengottai, and asked where my ancestral home was. I told him the same thing that I told the driver, to which he too responded like the driver did by referring to the agraharam.

My 5’6” frame shrank a tad.

Polite conversation required me to ask about his home. He said it was near the corporation office.

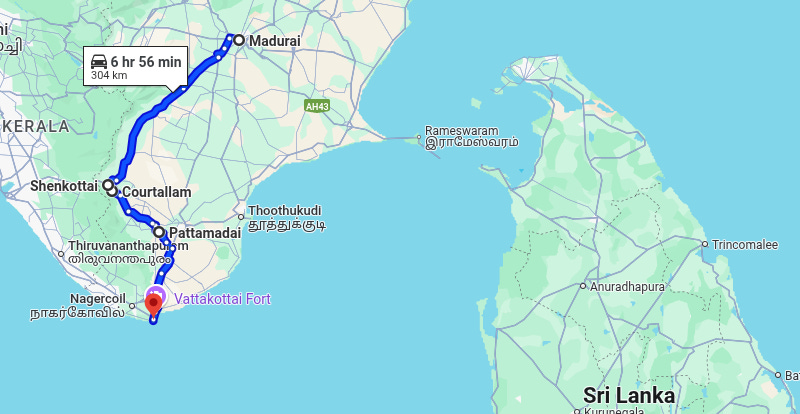

We drove out towards Pattamadai, with the cape—Kanyakumari—as the final destination. Pattamadai is where my other paatti—my paternal grandmother—lived.

As we reached the turnoff from the main road, I barely began to give directions to the driver when he said that he knew where the agraharam was in the village.

He said that word again, a word that I had hoped he wouldn’t say.

So, what is my problem with agraharam?

It comes with all the caste baggage.

Agraharam is a word that means only one thing: The part of the settlement—village or a small town—where only brahmins lived. It was spatial exclusion, if I were to revert to my academic way of thinking. If one’s ancestral home was in an agraharam, well, then the person’s people were brahmins. When people know that my grandparents lived in an agraharam, then they immediately know that I was raised in a brahmin family, even if I do not present myself as one.

An agraharam was typically anchored by a temple at one end of the street, almost always a temple that was dedicated to one of the variations of Vishnu. At the other end of the street is a Shiva temple. The houses were built one after the other, each sharing a wall with the neighboring house, like in the following photos of the agraharam streets in Sengottai.

In the bad old days, only brahmins, who occupied the highest tier in the awful caste system, could live in an agraharam. Dalits, lower caste people, and non-Hindus, who collectively vastly outnumbered brahmins, could not live there. In fact, Dalits weren’t even allowed to enter the streets in the bad old days. Brahmins didn’t want to do any dirty work at home or in the farms that some owned, for which then they hired lower caste and Dalits who lived in the edge of the village. The labor had to enter the household through the backdoor and never through the front.

The layout of the villages made religion and caste explicit. Both grandmas lived in streets where only brahmins lived. The extended family with whom I interacted a lot were all brahmins. Brahmins who were friends with brahmins, and brahmins marrying brahmins.

But then it was a similar arrangement across the village, and across any village. Muslims lived in one part of the village, Dalits lived in another area, the craftsman caste population lived in an area of their own, … Caste and religion determined where one could live in a village.

The older I got, and especially after getting to America, the more I thought about all these. It was not at all difficult to imagine and understand how much caste played a huge role throughout my life in the old country. The fact that my brahmin grandfathers went to school, and then to college, made it easy for me to work my way to the United States. The geographic accident of birth determined one’s caste and, thereby, one’s life trajectory too. Had my ancestors been Dalits who lived in a different part of the same village ... ?

Thankfully, the bad old ways are changing, though nowhere as rapid as I would like the changes to happen. Now, the residents of the agraharams in grandmas’ villages are not all brahmins. There are Hindus from other castes too. In a YouTube video about Sengottai that was shared widely among the extended family, I saw one person with a black abaya. I do not know if she was a resident or someone merely passing through. But, a Muslim woman even merely walking through an agraharam is a wonderful advancement over the bad old days.

The changes are also catalyzed by economic forces. As brahmins moved to towns and cities, and even to other countries, they had no choice but to sell their homes to buyers who are not brahmins. In a country with a tremendous shortage of housing, buyers too are ready to move to neighborhoods that were once off-limits to them.

All in all, these are the proverbial small steps towards progress in the agraharam. I hope that the giant leap towards overlooking differences in society is only a few more years away.